No products

Senatore Cappelli – History and Creator

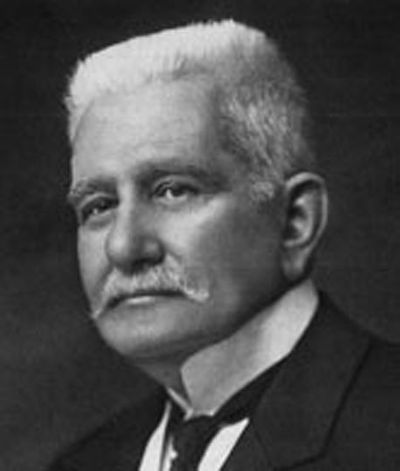

When, in 1906, Marquess Raffaele Cappelli, owner of several lands in Capitanata (nowadays called Province of Foggia, in Southern Italy), decided to designate one of them to the experimental cultivation, the Agriculture Minister provided him with the name of Nazareno Strampelli. The latter was an agronomist and geneticist, for years devoted to the hybridization of wheat species following Mendel theories. Strampelli accepted without hesitation the Marquess’ proposal.

Raffaele Cappelli

Before moving into the so-called Italy’s Granary, the scientist had held with little money an Itinerant Chair in Rieti. For his experiments, he was provided a piece of land quite far from the city and a stool. This did not placate his zeal and dedication.

Strampelli’s goal was simple: increase the harvest volumes. This was possible by creating wheat varieties resistant to bad weather and drought in the different climates. Without a doubt a noble intention since at that time many were suffering hunger pains. The first wheat species that the scientist introduced faced strong oppositions, both for the established tradition and opposition of seed producers.

Nazareno Strampelli with his wife Carlotta

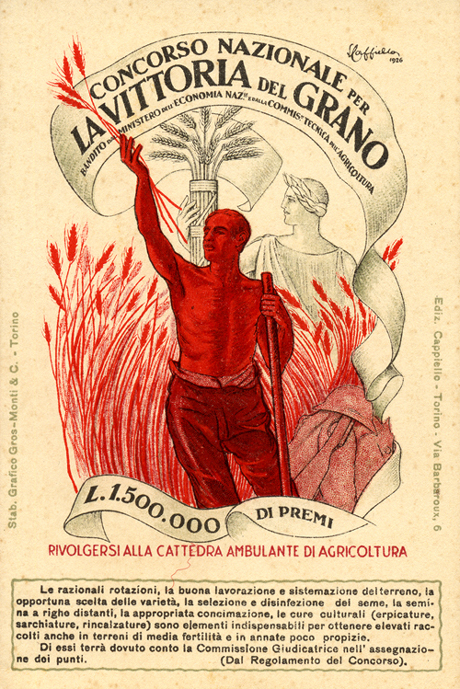

The Fascist regime changed the situation. Mussolini himself visited Strampelli to evaluate the scope of his discoveries. At that time Italy imported a considerable part of wheat from the U.S. and Soviet Union. Strongly believing in the scientist, the Duce initiated The Battle for Grain, decisive step towards the autarchic project.

King Vittorio Emanuele III, Mussolini and Strampelli visiting an experimental field

Lionetto Cappiello, propaganda manifesto for The Battle for Grain, 1926

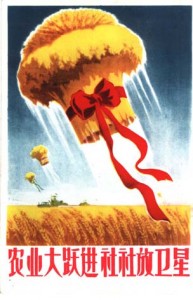

In less than 6 years the battle was won: concerning the wheat, Italy became independent. The high use of “elected seeds” was one of the key factors of the victory. The regime heavily honored Strampelli, naming him senator. But the agronomist, little interested in politics, wrote a letter to Mussolini declining the offer. His request was rejected and in spite of the charge was officialized. Strampelli continued to assiduously dedicate himself to his studies. In a short time the wheat varieties he developed spread worldwide, going so far as causing an analogous battle for grain, in the opposite way, in the Maoist China.

Chinese propaganda manifesto for the Battle of Grain

Strampelli never patented his studies, an operation that would have make him very rich, and he refused the privileges derived from the State credits awarded to him. Although he was aware of the value of his studies, he did not go into detailed auto-celebrative publications. In this respect he affirmed:

The man who everyday spreads his supremacy on everything that surrounds him is not owner of the time, the great gentlemen that fixes everything. I missed the time to do a lot of things that I wish to see accomplished. My publications, the ones to which I really care, are my grains. It does not matter if they do not bring my name, but to them is and is left my modest work.

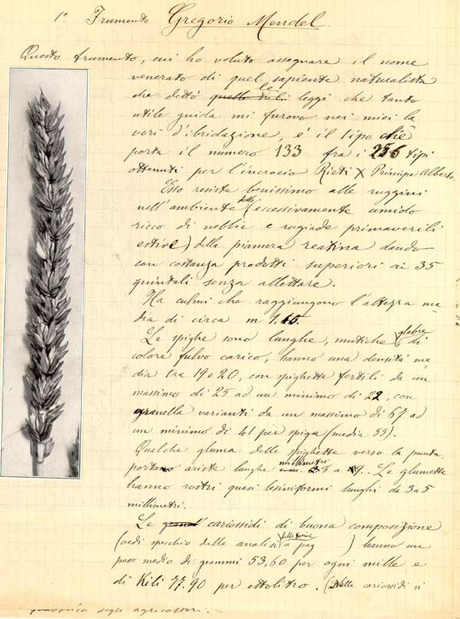

Original data sheet of the wheat variety “Gregorio Mendel”

Against his will, is lawful to treat Strampelli as a pioneer of the Green Revolution: that revolution that in few decades brought to the loss of biodiversity, to an increased pollution and also to the use of GMO. Also his noble scope has been set aside: nowadays the multinational companies keep the patents of the new species making them often sterile to force the farmers to the continuous procurement and dependency. Certainly the scientist would have firmly opposed to that.

For productivity purpose Strampelli’s seeds have been replaced as well. He developed more than 60 varieties each with a different name: Carlotta, in honour of his wife who was also his loyal assistant, Gregorio Mendel, Dante and also Stamura, Apulia, Alalà…

The agronomist did not forget the marquess, who also became senator, who years before provided him with a field. In this way was born the wheat “Senatore Cappelli” which became one of the most widespread, but nowadays cultivated only in few Italian regions, it can be considered a rare and refined variety.

Nazareno Strampelli